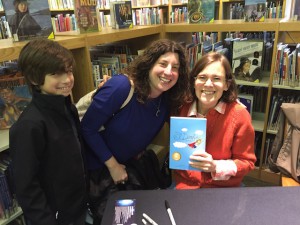

It’s not often I get to tell an author in person how much her work means to me. I had the opportunity to do this recently when I went to Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures Kids and Teens with my son to see Cece Bell.

Cece is an author and illustrator currently on tour for her graphic memoir El Deafo. Among the many accolades it has received, it was listed as one of the the NYT Notable Children’s Books of 2014, NYT Notable Middle Grade Books of 2014, and is a 2015 Newbury Honor book. What’s great about all of this attention is that this book has entered the public consciousness.

When my parents gave it to me soon after its release, I hadn’t heard of it. I actually kept it on the shelf for a long time, assuming it was about a deaf person who used sign language to communicate. Every time my parents visited, my mom would ask, “Have you read El Deafo yet?” When I finally admitted my reason for procrastinating, she told me it was actually about a deaf person who spoke and read lips. Well, then!

I gave the book five stars on Goodreads. My review:

When my mom loaned me this book to read, I was reluctant because I assumed it wouldn’t show the speaking deaf perspective and would be all about sign language. It’s ironic that I made the same mistake that everyone else makes about me (assuming I sign), but in my defense, it’s rare that this perspective is shown – and with such poignancy and humor. I kept saying “Yes!” out loud because I could relate to many of Cece’s experiences. Unlike Cece, however, I hated the Phonic Ear. I used to always complain, “Just because it makes it louder doesn’t mean it helps!”

I’m glad Cece learned how to share her superpowers and be comfortable with them, but I couldn’t help but cringe a little at how her classmates “used” her.

The note from the author at the end is also on point.

I made my kids read the book too, because I wanted them to get a better sense of my childhood. Cece’s book illustrates in wonderful detail what it was like to lose her hearing from meningitis at the age of four, and follows her ups and downs through elementary school.

A speaking deaf friend of mine also gave this book five stars. We both liked it more than our kids did. In her review, she wrote, “I expected to be disappointed by the book, figuring it would go down the all-to-predictable path of sign language. However, it turned out to be a very realistic representation of what some of my childhood was like. Cece tried sign language but it didn’t resonate with her and I believe this is the first time I have ever seen sign language mentioned in a book (fiction or non-fiction) on deafness where it wasn’t portrayed as a major part of the deaf person’s life. This book will go a long way to dispel stereotypes that every deaf person signs.”

The note from the author at the end that I referenced? Cece writes about differences in deafness – the cause and level of deafness vary, and so does communication. She talks about the Deaf community, or Deaf Culture, where sign language is the main mode of communication and deafness is viewed as a condition that shouldn’t be fixed. Deafness is considered their main identity, whereas for people like me and Cece, it’s just one part of who we are. In her note, Cece emphasizes that her experience is hers alone.

This is why I was surprised when she shared a different point of view in her talk. She said the school she attended — which had other deaf children — believed in only teaching them how to speak and lipread. They felt if sign language was taught, it would be a crutch. Cece said she doesn’t agree with this now, and wishes she had learned sign language. During the Q&A phase, someone asked what the Deaf Culture reaction was to her book. She admitted that she was scared for the potential fallout. Maybe she made this comment about sign language to appease those folks, but I wish she had tempered it a bit. Especially since research shows that the mostly signing “total communication” approach just isn’t as successful as other modalities.

One of my friends — a parent of two deaf boys with cochlear implants — attended the talk with her older son and had a similar reaction as me. She felt this was a somewhat careless way to appease Deaf Culture. “My (admittedly biased) perspective is that she wouldn’t be where she is now if she’d learned sign back then,” she said. “I truly believe [my son] wouldn’t be where he is now if he’d gone to a sign language program. I wish she had just stuck with ‘everyone has their own story and this is mine.'”

Exactly.

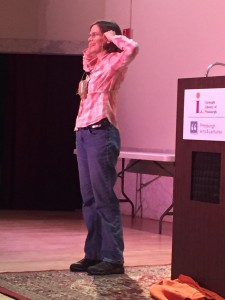

Otherwise, Cece’s talk was great. She had the audience laughing throughout. She started off with an experiment. When her back was turned, we all yelled HELLO! as loud as we could at the count of three. With her hearing aids on, she heard us. Then we did it again, with her hearing aids off. Naturally, she couldn’t hear us. I think a better experiment would have been to have some volunteers play the game of Telephone to demonstrate how difficult lipreading can be.

I got to see my nemesis, the Phonic Ear, again as Cece actually had hers from childhood. She put it on to show how bulky and embarrassing it was to wear.

Cece was asked why she wrote her memoir in graphic novel form. She said it was the perfect medium to tell her story because of the speech balloon, which allowed her to visually show what life can be like for a deaf person. An empty speech balloon, for example, shows that little Cece isn’t hearing anything. A panel with the audiologist has him saying, “RAAY YOE HANN WAH OO EER AAH BEEP!” And one of my favorites is the panel in which he adjusts the dial on her FM system and the text shows the volume increasing by going from light to bold.

An audience member asked why Cece used bunnies instead of people. She explained that it’s a great visual metaphor for hearing loss: ears that stand out, especially with the cords and ear molds going into them. Teachers often forgot to turn their microphones off, so Cece was able to hear them in other parts of the building, like the bathroom. Because of this, she began to think of her deafness as giving her superpowers.

Interestingly, Cece wasn’t comfortable with her deafness until recently; she didn’t like to advocate for herself. But an incident at her local Kroger turned things around and started her on the path to writing El Deafo.

A boy in the audience asked if she planned to write a sequel (stealing my question!). She said she has lots of ideas but hasn’t done anything yet.

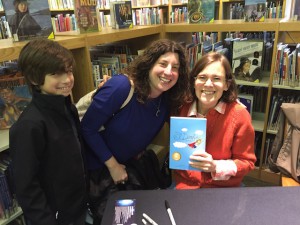

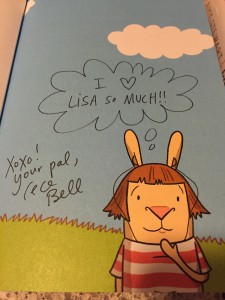

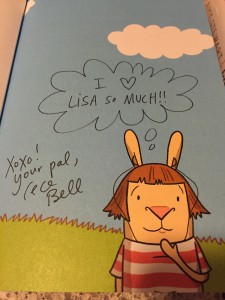

After the talk, we waited in line for a long time to get her autograph, but it was worth it. I told her that I was born three years after her in the 70s, and that her book was meaningful because it mirrored a lot of my own experience. Gesturing to my son, I said that it was great having my kids read it to gain a better understanding of my childhood.

She asked what I wear, and I told her a cochlear implant and hearing aid. I alluded to the fact that she’d benefit more from a CI than me, because (unlike me) she was post-lingually deafened.

I also encouraged her to write a sequel. Every stage of life brings different challenges, and I’d love for El Deafo to continue to educate and entertain.

I’m a writer, but not an illustrator. Cece is both, and I thank her for bringing our shared experiences to life in a way that I never could.